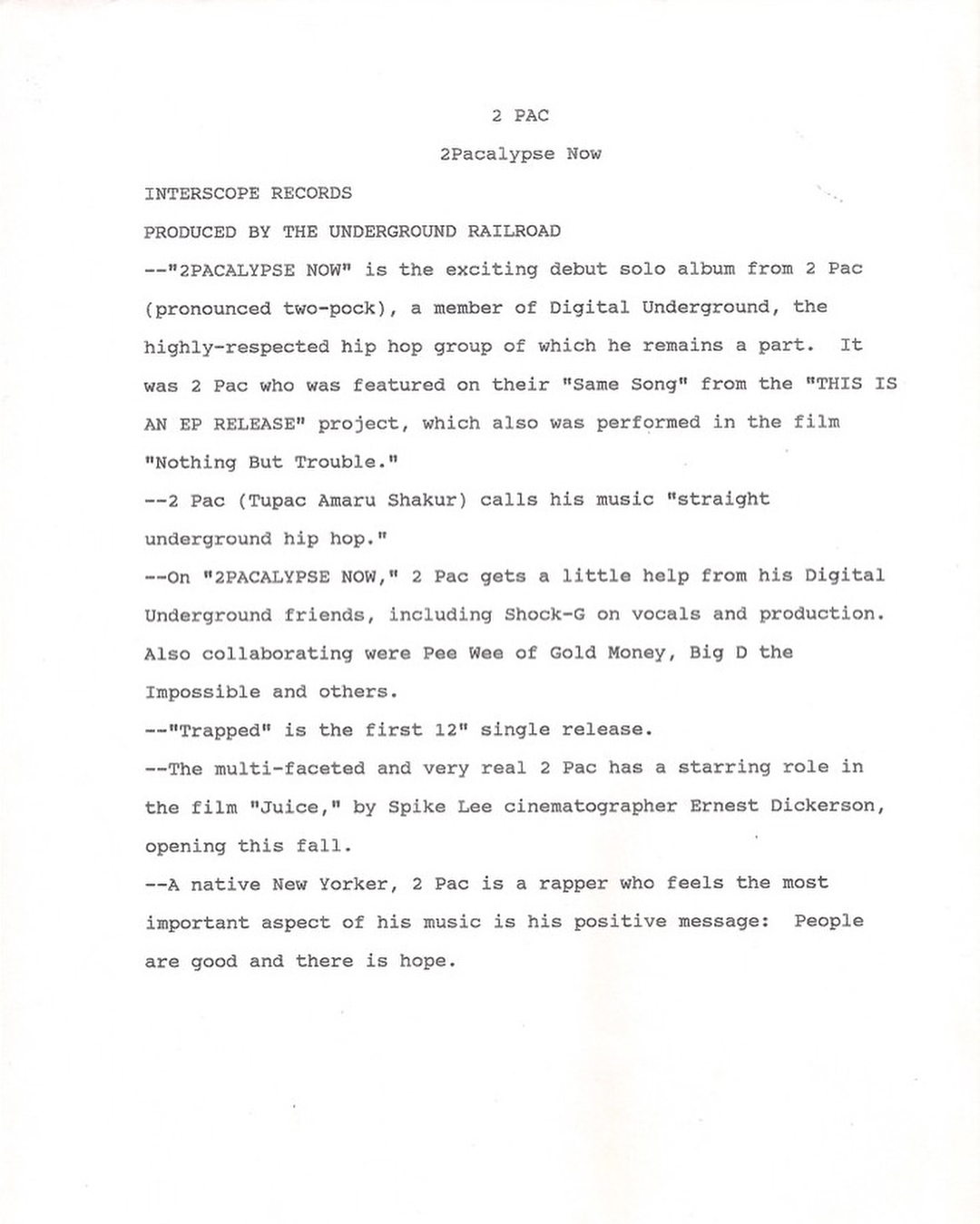

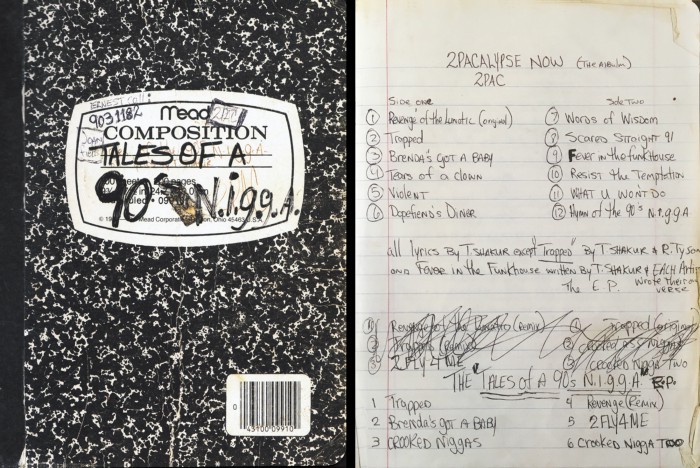

Some of the earliest words music fans heard from 2Pac that were not in a song were in the press biography that accompanied publicity copies of 2Pacalypse Now in late 1991. Journalist Sal Manna had been commissioned by Interscope Records to interview the relatively unknown rapper and write his biography. No agenda, no preconceptions. No subject too controversial, no holds barred. The two of them sat down on August 21, 1991 at a San Fernando Valley house where 2Pac and his mother Afeni were living. No manager, no posse, no record company. Just 2Pac and the interviewer in a room together. This was the beginning of his career—so early, in fact, that neither Interscope nor Afeni were sure whether 2Pac was one word or two, and went with 2 Pac in the original draft. The resulting biography and cut-by-cut, in which 2Pac talked about each song on the album, were both fiercely confrontational and shockingly insightful. This was 2Pac at 20 years old, yet much of what he said then is still true today, 25 years later.

“Life for the Young Black Male is hard, it’s not ‘The Cosby Show,’” says underground hip hop’s 2Pac. “I’m not perfect, I’m not half good, I’m all bad. The Young Black Male can identify with me and all that pain growing up poor. We need someone who’s been through that and narrowly escaped. We need someone who’s still in the streets, someone who stands for something.” That’s the straight Word is Bond from 2Pac (pronounced two-pock, whose full name is Tupac Amaru Shakur), an intensely outspoken and charismatic member of Digital Underground. On 2Pacalypse Now (Interscope Records), his provocative solo debut album, the rebellious 20-year-old challenges not only American society and the Young Black Male but the rap audience as well. “2pacalypse Now is a battle cry,” he explains, “a no-bullshit record about how we really live, really feel. Hip hop’s a mirror reflection of our culture today. Everything put on wax will be remembered and ‘Pray’ is not how we’re living in the ‘90s. It’s up to the rap audience to decide the future of rap music. If you want it to be that bubblegum ‘Ice, Ice, Baby’ bullshit, that’s what it’s gonna be. But if you want it to be real, you have to stick with the real NIGGAs. If not, they’re going to take this industry away from us. It’s gonna be a white thing, just like they did with rock ‘n’ roll. I’m speaking truth. We’ve got to stand strong.”

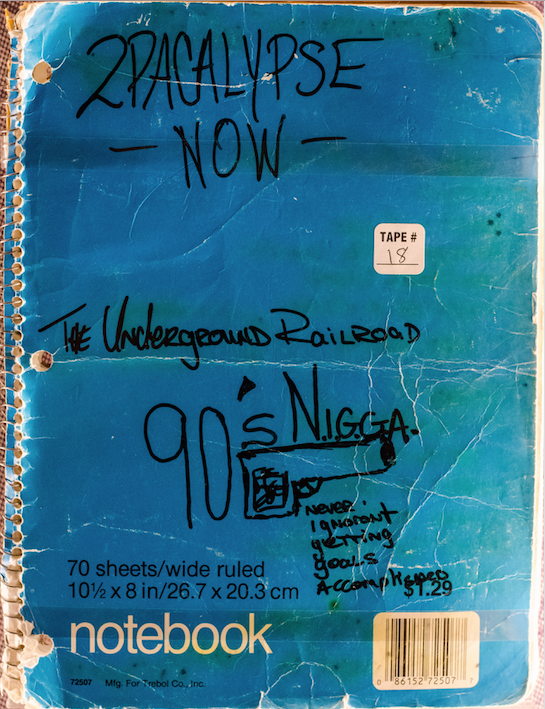

For 2Pac, NIGGA means Never Ignorant Getting Goals Accomplished. 2Pac is and has. His life has been very real from the start. His mother, a Black Panther, was pregnant with him when she was sent to jail on suspicion of conspiracy to blow up the New York Botanical Gardens. “I was in jail even as a fetus,” says 2Pac. “So I have no mercy for the system.” Still, his mother acted as her own attorney and beat the case. His father? He died the day after he got out of jail. His stepfather? On the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list. A godfather? Famed Panther Geronimo Pratt. Says 2Pac, “All my heroes have been in jail.” After being born and raised in a rough-and-tough section of New York City, he moved with his mother to the impoverished ghettos of Baltimore, where he attended the High School of Performing Arts to learn to become an actor. “I saw black people on TV and thought maybe I could be one of the few”, he recalls. But when a high school friend was shot and killed while playing with guns, he was inspired to write and perform his first rap. The gun control rhyme quickly spread his name around the city and he decided to find his future in music. Dropping out of high school (he later earned his G.E.D.), he set out for Northern California. “There’s supposed to be palm trees, sand and easy money,” 2Pac says with a laugh. “It ain’t so.”

Two years ago, he found himself homeless and hungry, sleeping on a public bench in The Jungle—Oakland, California. In desperation, he turned to “a rough crowd, a mix of bad people. But everyone around me now had money. Anti-drug? I’m anti-poverty. All this ‘drop the weapons, drop the dope’ don’t work. I want to tell that man out there that he can’t sell drugs but I can’t—because he’s got a family to feed. You have to give people more. They have to see a purpose to life. When you’ve never had shit, you have nothing to lose. I was lost, so what?” “Let’s face it, the war on drugs is a war on us. How dumb can the American public be? You can’t wage war on inanimate objects. There’s no poppy fields in my neighborhood. It’s a war on the Young Black Male, we’re who they’re locking up.” Though he began giving out tapes of his raps and performing, he admits he never thought he’d make it big. But finally he got his break—and was invited to audition for Shock G from Digital Underground. Shock liked what he heard but 2Pac would have to earn his way on stage. “He told me, ‘Come on the road as a roadie and by next year everyone will know who you are.’ He’s been Word to the Mutha.” Still, following months of roadwork, 2Pac had yet to appear in concert. Then someone tried to kill him: After talking peace on stage during a solo appearance at a Martin Luther King, Jr. festival, his pursuer shoved a 12-gauge in his face and almost succeeded in snuffing him. 2Pac immediately gave Shock an ultimatum: “Yo! Let me rap or I’m leaving. And Shock came through. If not for him, I would’ve gone down.”

2Pac was featured on Digital Underground’s “Same Song” from the This Is An EP Release project, which was also performed in the film “Nothing But Trouble.” Today, the folks who were trying to kill him are fans. “When you’re rapping you gain a posse and make more friends. Now they come to get an autograph.” It may soon be the autograph of not only a music star but a movie star too. 2Pac has a major role in “Juice,” a film written and directed by Spike Lee’s cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, which will open on the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday in late January. The story is that Money B was going to an audition and 2Pac simply hitched a ride to somewhere else. But as Money read the script, he started teasing 2Pac that one of the characters acted just like him. When they got to the audition, 2Pac asked if he could read for the part and immediately won the role of the villain, the best friend-turned-murderer. Ironically, he’s become the actor he started out to be. However, 2Pac remains a staunch member of Digital Underground. “D.U. is an empire not a group,” he points out and he’ll be heard on its next album, Sons Of The P (Meaning Parliament or Panthers).

Staying true and sticking together is important to 2Pac. 2Pacalypse Now was produced by what he calls The Underground Railroad (an overall title that includes himself, Big D the Impossible, Shock G, Pee Wee, Jeremy, Raw Fusion and Live Squad). “It’s like when Harriet Tubman took the slaves north. Dope dealers are like slaves, trapped, and rappers are like conductors on this underground railroad taking them to something better. In my posse I’m talking about brothers who used to be kingpins. They trust me so I got to be large. What I get, the homies get too. I’m down for the Young Black Male. Like on the movie, the actors were bringing other black actors to the set—I was bringing my friends from the street. That worried a few people. But I live what I say. I’m not no teacher, as you can tell from how I speak. I’m just a voice from the crowd.”

His is a voice of reality. “In the ‘90s you don’t have to wear beads or no kinte cloth to be African. Africans are living in the ghettos! They can’t afford that kinte shit. It’s time to be real.” “I’m not bragging about being from the ghetto,” he continues. “There’s nothing to brag about. These aren’t gangster raps. Gangsters are a fairy tale. The only reason they’ve got the confidence of the Young Black Male is because they’re the only ones who shoot back—like the Panthers in the sixties. I’m not a gangster, I’m a NIGGA, I’m from the underground. I can’t front. To say that I’m ‘hard’ is too fashionable. I’m not hard, I’m soft. Life’s made me crazy soft. If you hit me, I’ll fall.” On the street, 2Pac wears his gold and packs a pager like a dealer even though he’s not. Why? “I’m not turning the other cheek. The streets are dangerous and so I have to be. But that doesn’t mean you can’t have fun either. The slaves were still singing. I love it when cops sweat me—because I’m legit. I’m the wrong one, even though I look this way, and so they have to turn me loose. I want to show it’s cool to be legit. I want a positive image—to take the bad and turn it to good, to music.”

His is a voice of hope. “The Young Black Male hero is already in us!” Every white kid wants to be us! Americans tried to kill us and we’ve gotten the worst revenge because now we got their kids wanting to be us! I see it at every rap show—and that’s excellent. If the white adults can say, ‘My son can kick it with that man,’ maybe they’ll see what’s going on for real. That’s the power of rap and once was the power of rock ‘n’ roll.”

It’s the power of the streets. It’s the power you can’t control. It’s the power of 2Pac.