Nick Broomfield has released a follow up to his 2002 documentary, Biggie and Tupac, this time focusing on Suge Knight, while still of course referencing what happened to Tupac and Biggie. In that regard it’s very much a sequel of sorts. Below is a review from The Guardian, who give it a 4/5 star review.

Nick Broomfield has released a follow up to his 2002 documentary, Biggie and Tupac, this time focusing on Suge Knight, while still of course referencing what happened to Tupac and Biggie. In that regard it’s very much a sequel of sorts. Below is a review from The Guardian, who give it a 4/5 star review.

Nick Broomfield revisits the deadly hip-hop beef he covered in 2002’s Biggie and Tupac and uncovers deeper truths about America

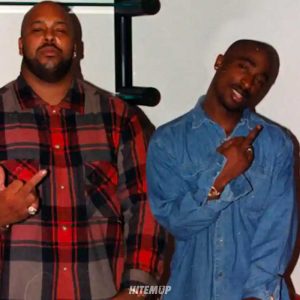

Amid a bleakly compelling film, the climactic scene of Nick Broomfield’s Biggie and Tupac, released in 2002, was particularly memorable. Mostly for the palpable air of menace exuded by the hulking hip-hop magnate Suge Knight as he prepared to sit down with the mildly flustered documentary-maker. Particularly because Knight – who had been head of Tupac’s record label, Death Row Records, and was accused of being involved in the murder of at least one of the rappers – was in prison at the time and guards were nearby. What could he possibly do? And yet his charisma and presence were potent.

Almost two decades on, Knight’s hold on the imagination of those around him has waned. After a spell on the outside, he’s now back in prison. He’s 56 now, and while you still wouldn’t trifle with him, that’s the kind of age at which a man might start to regret making so many enemies. People aren’t so scared of Suge Knight any more. They’re starting to talk. Accordingly, Bloomfield has returned to America for another poke around inside a double murder case that has seemingly puzzled the finest minds of the LAPD for more than a quarter of a century.

The truly fascinating details in Last Man Standing (BBC Two) aren’t the obvious ones. The minutiae of the absurd, lethal beef between Knight and his protege Tupac Shakur on the west coast and Sean “Puffy” Combs and Biggie Smalls on the east now seems too petty to bother explaining. The killings themselves were an exercise in tit-for-tat pointlessness; the banality of evil. Instead, the murders are a means to explore a world with its own mindset and value system.

As ever, Broomfield’s apparent mildness is his greatest weapon; the unsteadily dangled boom mic is mightier than the glock. There’s privilege in being able to let your guard down, and Broomfield exploits that to the full. In this milieu, his strength lies in what could easily be his weakness – his upper-middle-class Englishness and air of underdog amateurism. As he leans into them, however, he makes these characteristics work for him, rendering himself unthreatening. People evidently like confiding in him, even when they’re surprised to find themselves doing so.

What he elicits is a sort of elegy, and a documentary marinated in regret. As well as the rappers’ nearest and dearest, he speaks to gang-affiliated bodyguards – still grimly wary but, in some cases, penitent now. “I can’t do nothing but apologise for the way I lived,” says one. Eventually, it becomes clear that what Broomfield is revealing isn’t so much the truth about the crimes (though as new facts emerge, it becomes harder and harder to imagine any way of them happening that doesn’t implicate the LAPD), but certain truths about America.

America, as we know, still eats its young. Particularly its black young. The version of success aspired to by the likes of Knight and Shakur was a direct result of the systemic disadvantage into which they were born. It’s a cold, bleak loveless state; all present and no future; all style and no substance. “Tupac wasn’t a gangster,” says Yaasmyn Fula, informally known as Tupac’s second mother. “He wanted to address poverty, despair and drug addiction.” Instead, through his toxic association with Knight, he found himself living out society’s dearest yet also cheapest fantasies. His horizons narrowed with success, becoming more corrupted and paranoid.

The film isn’t a whodunnit. The questions it poses are more to do with how these lives could have played out in a healthier society. One of Knight’s Death Row Records security detail, Mob James, suggests that “instead of being the businessman he should have been, Suge turned into one of the homies”. In other words, a man who probably possessed the acumen to succeed conventionally was seduced by dead-end glamour. If you’ve had to fight your way up from the bottom, sometimes you forget there’s a moment to stop fighting. Sometimes, presumably, the fight becomes an end in itself.

But what of Tupac? “He was a very kind-hearted person,” recalls his friend Demetrius Striplin. “He got lost in the image of being tough.” Shortly after Shakur died, representatives of Death Row came and repossessed his fleet of expensive vehicles. No legacies were built. No fortunes were made that weren’t quickly squandered. Everyone who survived ended up more or less back where they started. Broomfield leaves us with a brief clip of Tupac and Biggie, in younger years, freestyling together. They look excited, happy, unguarded. What a waste.

Leave A Comment